However, according to the Rocky Mountain Institute demand charges “are a significant barrier to the development of viable business models to operate public DCFC networks.“

Most commercial customers pay for both demand and consumption. Most residential customers only pay for consumption. Customers on demand charge tariffs pay for the highest rate of energy use they reach – the peak demand – in each billing cycle.

Demand, also called load, refers to the rate at which energy is used at any given moment. Consumption, also called usage, is the amount of energy used in each billing cycle. Some other utilities are lobbying their state utility boards to allow them to charge residential customers demand charges to provide similar price signals.Ĭustomers pay for electricity in one of two ways: consumption, measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh) and demand, measured in kilowatts (kW).

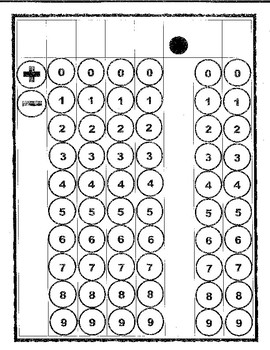

#Gridable with place value drivers#

Several utilities, including Pacific Gas & Electric, San Diego Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and Hawaiian Electric, are already experimenting with time-of-use charges to send price signals that push drivers to charge during off-peak times. The concern with EVs – particularly EVs charged with direct current fast chargers (DCFCs) – is that they will create higher peak demands than the grid can provide. Both options are more expensive than operating base load power plants during times of lower demand.ĭemand charges and time-of-use charges are used to pass those costs on to consumers. To meet high demand utilities either have to activate peaking power plants or buy energy from other utilities. For example, during hot summer afternoons demand is much higher than most other times because of the need for more air conditioning. Demand isn’t constant, however it varies depending on what customers are doing. Utilities need to match the supply of generated power with their customers’ demand for power. But if those EVs charge around the same time, especially during times of overall peak demand, utilities won’t be able to meet the demand. Utilities theoretically have the excess generation capacity to power around 75% of America’s vehicles if they were EVs. Rapid chargers, in particular, draw very large loads. A single electric vehicle can draw as much power as three new houses. The increased demand EVs will place on the grid will be enormous.

in 2025.Īccording to EEI, approximately 4.4 to 5.5 million charging ports, including Level 1 and Level 2 chargers in homes and workplaces and Level 3 fast chargers in public charging stations, will be needed by 2025. That represents around 3% of the 258 million cars and light trucks expected to be registered in the U.S. The Edison Electric Institute reports that up to seven million EVs could be on Americans roads by 2025, up from a little over half a million in 2016, with continued sales of 1.2 million per year. Sales of electric vehicles are growing fast. EVs could usher in several significant changes to the grid that make it more distributed, more flexible, and smarter. Rather than causing widespread blackouts or increasing the cost of electricity, the actual change may be more of an evolution than an extinction. But the way in which the grid will be “killed” may not be what these authors had in mind. These authors have a point the electric grid wasn’t designed to handle a couple hundred million EVs charging every day. A number of think pieces have been published in the last few years asserting that mass adoption of electrical vehicles (EVs) might kill the electric grid.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)